Nicheformer: a foundation model for single-cell and spatial omics

Summary

In a preprint posted on bioRxiv on April 17, 2024, researchers from the Theis Lab, Technical University of Munich, and Helmholtz Munich introduced Nicheformer, a transformer-based foundation model that learns unified cellular representations from both single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data. This groundbreaking work, which is currently under review at Cell, leverages the massive SpatialCorpus-110M dataset, comprising over 110 million cells from diverse tissues and technologies, to capture the complex interplay between gene expression and spatial organization in tissues. Nicheformer demonstrates state-of-the-art performance on various spatial downstream tasks and enables the transfer of spatial information to dissociated single-cell data, opening up new avenues for biological discovery and understanding tissue function in health and disease.

All models described are implemented in a Python package, available at GitHub.

Introduction

Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics technologies have revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity and spatial organization within tissues. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables the profiling of gene expression at the individual cell level, revealing distinct cell types and states. However, scRNA-seq requires tissue dissociation, leading to the loss of spatial information. Spatial transcriptomics technologies, such as MERFISH, 10x Visium, and Slide-seq, preserve the spatial context of cells, allowing for the investigation of cellular interactions and microenvironments.

Despite the rapid advancements in single-cell and spatial technologies, integrating and analyzing data across modalities remains a significant challenge. Differences in experimental protocols, data sparsity, and the lack of a unified framework for joint analysis hinder the full utilization of these datasets. Foundation models, which have achieved remarkable success in natural language processing and computer vision, offer a promising approach to address these challenges in biology.

Foundation models are large-scale, self-supervised models that learn general representations from vast amounts of unlabeled data. These models can be fine-tuned for various downstream tasks with limited labeled data, enabling efficient transfer learning. In the context of single-cell biology, foundation models have the potential to learn a unified representation of cellular heterogeneity that captures both transcriptional and spatial information.

In this blog post, we will explore Nicheformer, a novel foundation model for spatial single-cell biology introduced in the paper “Nicheformer: a foundation model for single-cell and spatial omics” by Schaar et al. We will delve into the architecture of Nicheformer, its pretraining dataset, and its performance on various spatial prediction tasks. Furthermore, we will discuss the implications of Nicheformer for data integration, biological discovery, and the future of foundation models in spatial single-cell biology.

Nicheformer: A Novel Foundation Model for Spatial Single-Cell Data

Nicheformer is a transformer-based foundation model designed specifically for learning representations of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data. The model architecture is inspired by the success of transformers in natural language processing tasks, such as BERT and GPT, and adapts them to the unique characteristics of biological data.

Pretraining Dataset: SpatialCorpus-110M

One of the key strengths of Nicheformer is its pretraining dataset, the SpatialCorpus-110M. This dataset consists of over 110 million cells from both human and mouse samples, encompassing a wide range of tissues and organs. The data is sourced from various single-cell and spatial transcriptomics technologies, including 10x Genomics, Drop-seq, and MERFISH, among others.

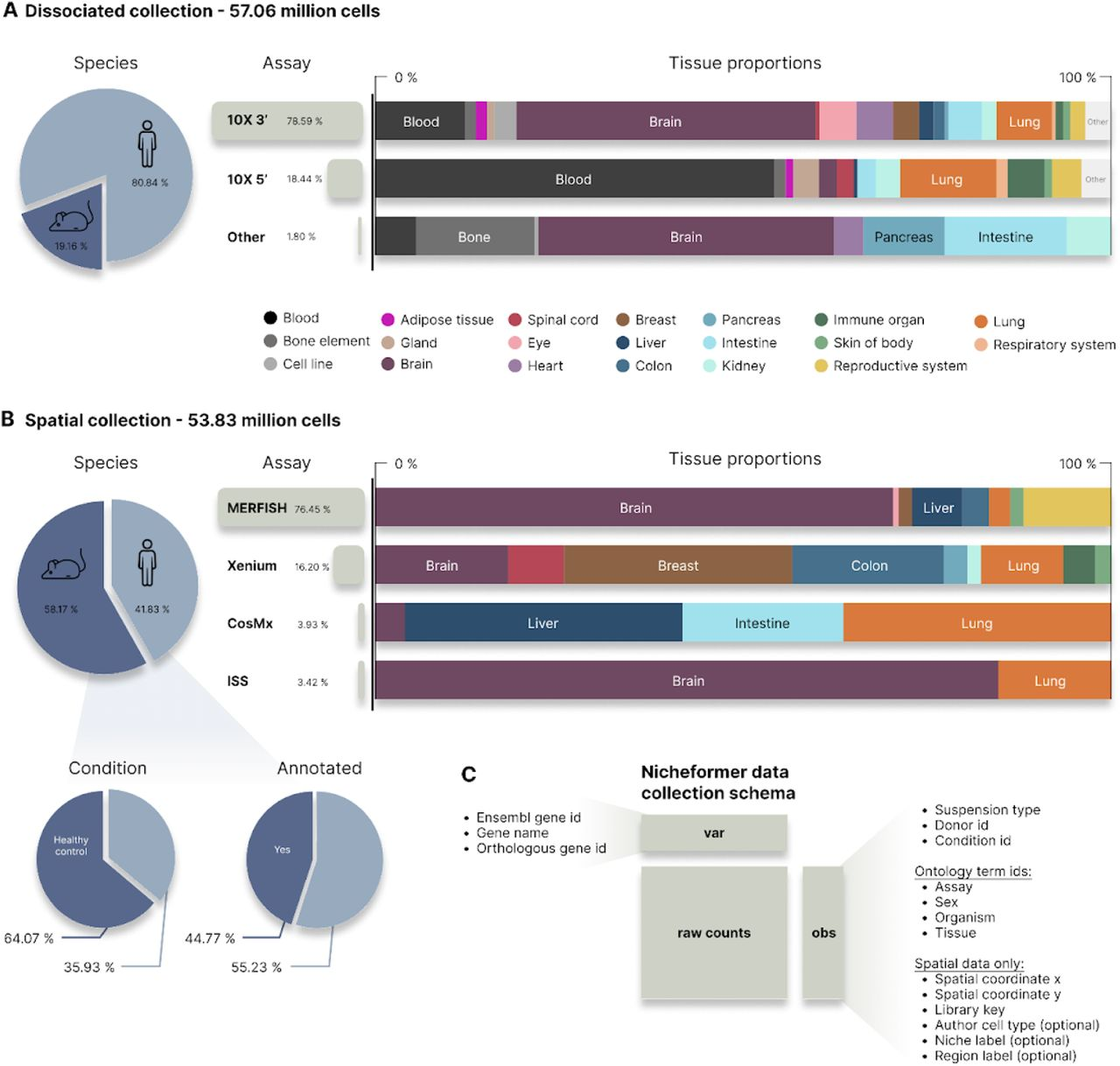

Fig. 2 in the manuscript provides an overview of the SpatialCorpus-110M, showcasing the diversity of tissues, species, and technologies included in the pretraining dataset.

The SpatialCorpus-110M is carefully curated and preprocessed to ensure data quality and compatibility. The authors have developed a standardized pipeline for data integration, including gene filtering, normalization, and batch effect correction. This enables Nicheformer to learn a unified representation of cellular heterogeneity across different experimental conditions and modalities.

Model Architecture and Pretraining

Nicheformer’s architecture is based on a multi-layer transformer encoder, which learns to map input sequences of gene expression vectors to a low-dimensional embedding space. The model uses a gene rank-based tokenization approach, where genes are ranked by their expression levels within each cell and assigned corresponding token IDs. This tokenization scheme helps to capture the relative importance of genes and reduces the impact of technical noise.

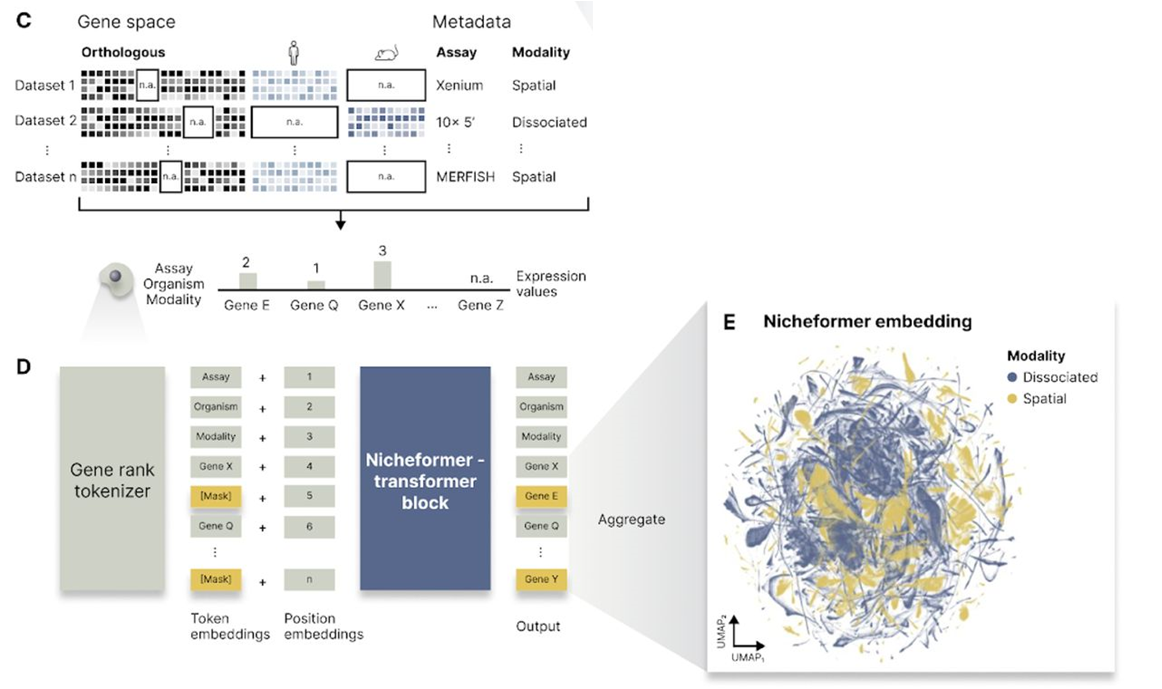

Fig. 1C, 1D and 1E in the manuscript illustrate the tokenization process and the architecture of Nicheformer, highlighting the use of contextual tokens for metadata and the 12-layer transformer encoder.

In addition to gene expression tokens, Nicheformer incorporates contextual tokens to encode metadata information, such as species, tissue type, and experimental assay. These contextual tokens allow the model to learn associations between gene expression patterns and biological contexts, enhancing its ability to generalize across datasets.

The pretraining objective of Nicheformer is based on masked language modeling (MLM), where a portion of the input tokens is randomly masked, and the model is trained to predict the original tokens based on the surrounding context. This self-supervised learning approach enables Nicheformer to capture intricate relationships between genes and cells without the need for explicit labels.

Comparison to Existing Methods

Nicheformer offers several advantages over existing methods for analyzing single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data. Traditional dimensionality reduction techniques, such as principal component analysis (PCA) and t-SNE, often struggle to capture complex nonlinear relationships in high-dimensional gene expression data. Variational autoencoders, such as scVI, have shown promise in modeling single-cell data but lack the ability to incorporate spatial information explicitly.

Nicheformer, on the other hand, leverages the power of transformers to learn a contextualized representation of cellular heterogeneity that integrates both transcriptional and spatial information. The model’s ability to handle variable-length input sequences and its attention mechanism allow it to capture long-range dependencies and spatial relationships between cells.

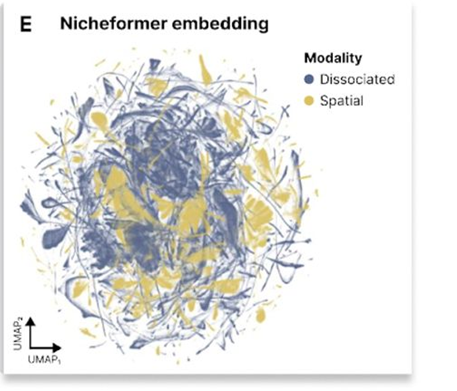

Fig. 1E in the manuscript shows a UMAP visualization of the Nicheformer embedding, demonstrating its ability to capture meaningful biological structure in the pretraining dataset.

Evaluating Nicheformer on Spatial Prediction Tasks

To assess the effectiveness of Nicheformer in capturing spatial information and its ability to generalize across datasets, the authors designed a set of novel downstream tasks specifically tailored for spatial transcriptomics data. These tasks aim to predict various spatial attributes of cells, such as their cell type, niche, and regional identity, as well as the composition and density of their local neighborhoods.

Cell Type, Niche, and Region Label Prediction

The first set of tasks focuses on predicting the cell type, niche, and region labels of individual cells based on their gene expression profiles. These labels provide a hierarchical categorization of cells, with cell types representing the most specific level, followed by niches and regions at increasingly broader scales.

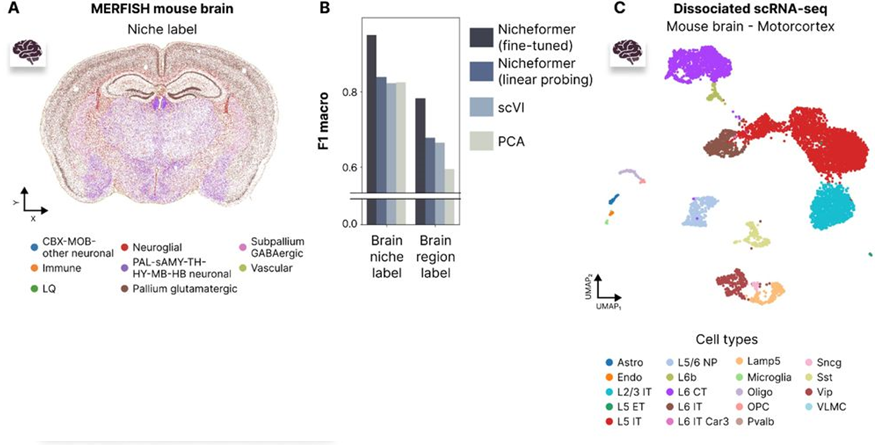

Fig. 3A, 3C in the manuscript illustrate the cell type, niche, and region labels used for evaluation in the MERFISH mouse brain dataset.

Fig. 3B in the manuscript shows the performance comparison between Nicheformer and baseline methods on cell type, niche, and region label prediction tasks in the MERFISH mouse brain dataset.

Nicheformer is evaluated in two settings for these tasks: linear probing and fine-tuning. In the linear probing setting, a simple linear classifier is trained on top of the frozen Nicheformer embeddings, assessing the quality of the pretrained representations. In the fine-tuning setting, the entire model is further optimized on the downstream task, allowing it to adapt to the specific dataset and labels.

The authors compare Nicheformer’s performance to baseline methods, such as scVI and PCA embeddings, using the same linear probing approach. Across all three label prediction tasks, Nicheformer consistently outperforms the baselines, demonstrating its ability to capture spatial information and generalize across datasets (Fig. 3B).

Neighborhood Cell Composition and Density Prediction

The second set of tasks assesses Nicheformer’s ability to predict the composition and density of local cell neighborhoods based on the gene expression of individual cells. These tasks are particularly relevant for understanding the spatial organization of tissues and the interactions between cells in their microenvironment.

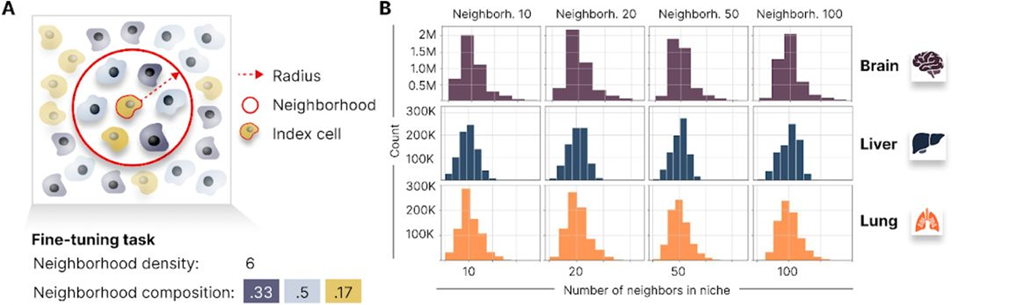

Fig. 4A and 4B in the manuscript define the concept of cell neighborhoods and illustrate the distribution of neighborhood sizes across different datasets.

For the neighborhood composition prediction task, the authors define a cell’s neighborhood as the set of cells within a fixed radius and compute the proportion of each cell type within that neighborhood. Nicheformer is then trained to predict these neighborhood composition vectors based on the gene expression of the central cell.

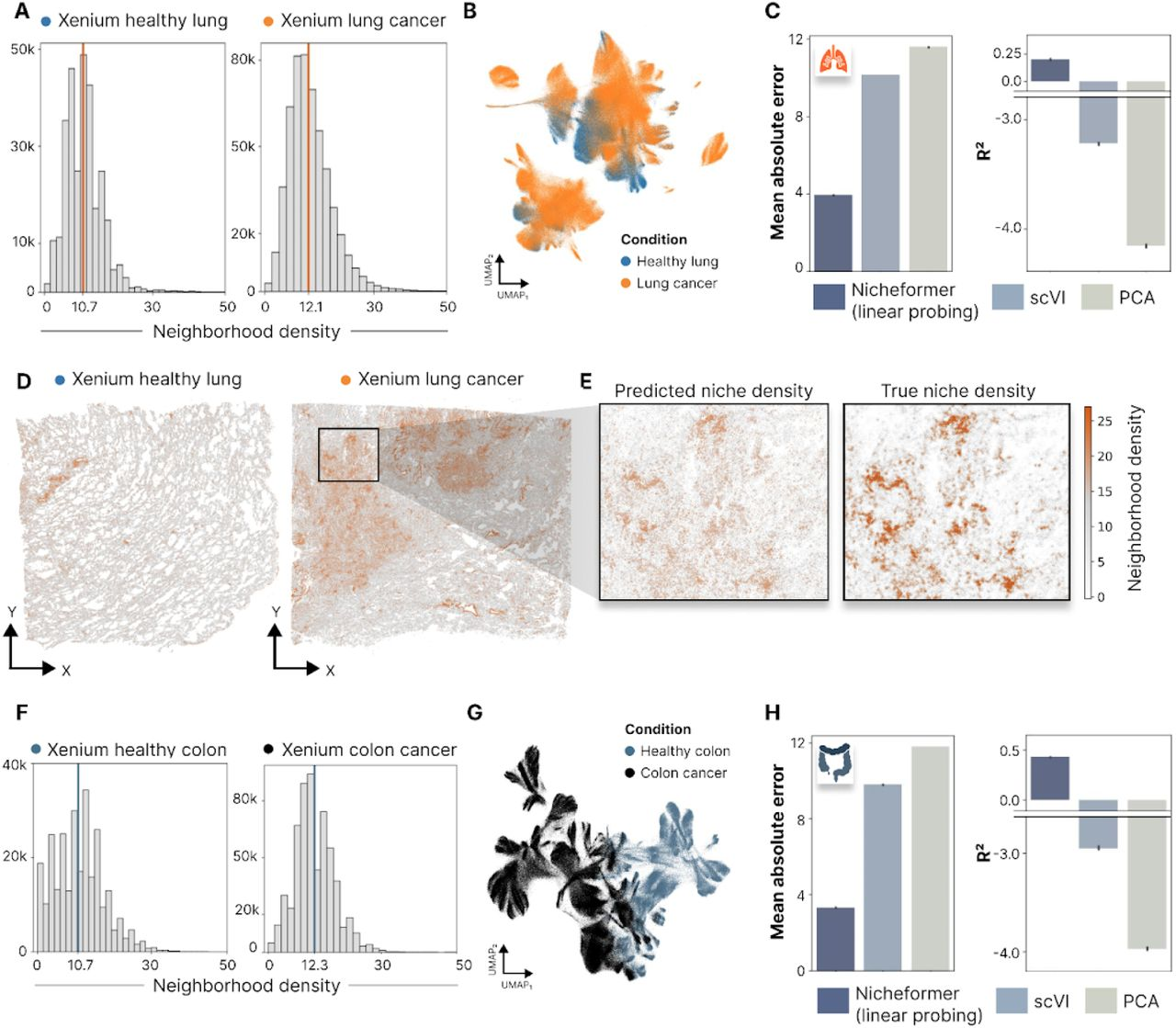

Similarly, for the neighborhood density prediction task, Nicheformer learns to estimate the total number of cells within a given radius based on the gene expression of the central cell. This task is evaluated on both healthy and diseased tissue samples, showcasing Nicheformer’s potential for identifying differences in cellular organization across biological conditions.

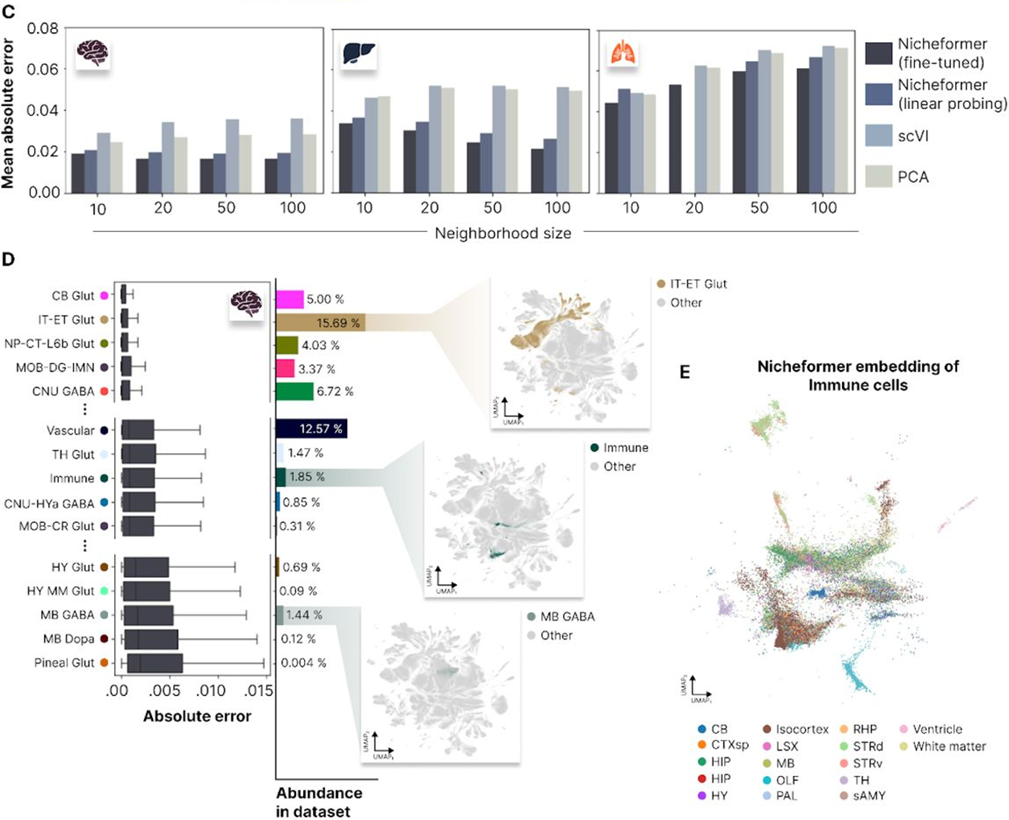

Fig. 4C and 4D in the manuscript present the performance of Nicheformer on neighborhood composition prediction tasks across different datasets and compare it to baseline methods.

The authors demonstrate that Nicheformer significantly outperforms baseline methods on both neighborhood composition and density prediction tasks (Fig. 4C and Fig. 5C, H). These results highlight the model’s ability to capture the spatial context of cells and its potential for uncovering biologically meaningful patterns in complex tissue architectures.

Fig. 5A-H in the manuscript show the performance of Nicheformer on neighborhood density prediction tasks in lung and colon cancer datasets, comparing healthy and diseased tissue samples.

Transferring Spatial Information to Dissociated scRNA-seq Data

One of the most exciting applications of Nicheformer is its ability to transfer spatial information learned from spatial transcriptomics datasets to dissociated single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data. This capability opens up new possibilities for integrating these two modalities and enabling the spatial annotation of existing scRNA-seq datasets.

Annotating Brain Region and Niche Labels in Motor Cortex scRNA-seq

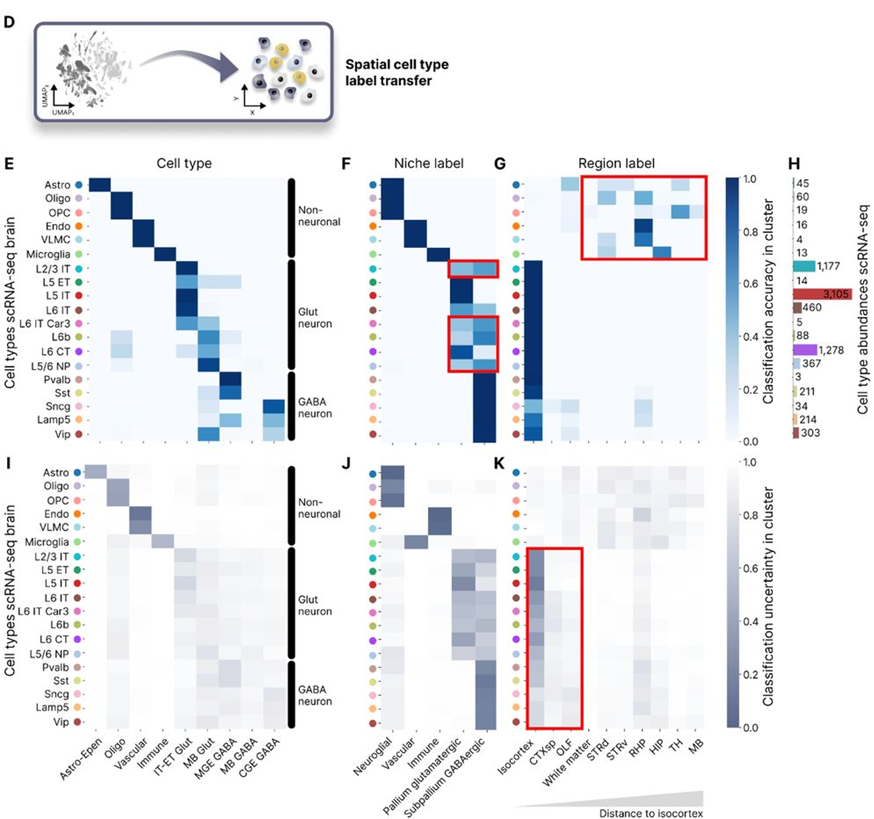

To demonstrate the effectiveness of Nicheformer in transferring spatial information, the authors focus on a case study involving the annotation of brain region and niche labels in a mouse motor cortex scRNA-seq dataset. The goal is to assign each cell in the scRNA-seq dataset a corresponding brain region and niche label based on the spatial patterns learned by Nicheformer from the MERFISH mouse brain dataset.

Fig. 3D-K in the manuscript illustrate the process of transferring brain region and niche labels from the MERFISH mouse brain dataset to the motor cortex scRNA-seq dataset using Nicheformer.

First, Nicheformer is fine-tuned on the MERFISH mouse brain dataset, which contains detailed annotations of brain regions and niches based on the spatial locations of cells. During this fine-tuning process, the model learns to associate gene expression patterns with specific spatial contexts.

Next, the fine-tuned Nicheformer model is applied to the motor cortex scRNA-seq dataset, which lacks spatial information. By leveraging the learned associations between gene expression and spatial context, Nicheformer is able to assign brain region and niche labels to each cell in the scRNA-seq dataset.

The authors evaluate the accuracy of the assigned labels by comparing them to the ground truth annotations available for the motor cortex scRNA-seq dataset. Remarkably, Nicheformer achieves high accuracy in predicting both brain region and niche labels, demonstrating its ability to transfer spatial information across datasets and modalities (Fig. 3E-G).

Furthermore, the authors analyze the uncertainty of the predicted labels, which provides a measure of confidence in the spatial annotations. The uncertainty analysis reveals that Nicheformer assigns labels with high confidence to cell types that are specific to the motor cortex region, while exhibiting higher uncertainty for cell types that are less regionally specific (Fig. 3I-K).

Implications for Data Integration and Biological Discovery

The ability to transfer spatial information from spatial transcriptomics datasets to dissociated scRNA-seq data has significant implications for data integration and biological discovery. By enabling the spatial annotation of existing scRNA-seq datasets, Nicheformer can help researchers gain new insights into the spatial organization of tissues and the role of cellular microenvironments in shaping gene expression patterns.

Moreover, the integration of spatial and single-cell transcriptomics data can facilitate the identification of spatially-resolved cellular interactions and communication networks. By combining the high resolution of scRNA-seq with the spatial context provided by spatial transcriptomics, researchers can better understand the complex interplay between cells and their microenvironment in health and disease.

Nicheformer’s spatial information transfer capability also has the potential to guide the design of future spatial transcriptomics experiments. By leveraging the spatial patterns learned from existing datasets, researchers can prioritize the profiling of specific regions or cell types that are likely to yield novel biological insights.

In conclusion, Nicheformer’s ability to transfer spatial information from spatial transcriptomics datasets to dissociated scRNA-seq data represents a significant advance in the integration of these two modalities. This capability opens up new avenues for biological discovery and has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of tissue organization and function.

Discussion and Future Directions

Nicheformer represents a significant step forward in the application of foundation models to spatial single-cell biology. By learning general, spatially-aware representations of cellular variation from large-scale datasets, Nicheformer enables the integration of diverse data modalities and the discovery of novel biological insights. However, there are still several challenges and opportunities for future development in this rapidly evolving field.

Significance of Nicheformer for Advancing Spatial Single-Cell Biology

The success of Nicheformer in capturing spatial information and transferring it across datasets and modalities highlights the potential of foundation models for advancing spatial single-cell biology. By leveraging the power of self-supervised learning and large-scale pretraining, Nicheformer can learn a unified representation of cellular heterogeneity that captures both transcriptional and spatial variation.

This spatially-aware representation can serve as a powerful tool for guiding experimental design and enabling more nuanced analyses of cellular function in the context of tissue architecture. For example, researchers can use Nicheformer to identify spatially-resolved cellular interactions, prioritize the profiling of specific regions or cell types, and investigate the role of cellular microenvironments in shaping gene expression patterns.

Limitations and Future Improvements

Despite the impressive performance of Nicheformer on various spatial prediction tasks, there are still several limitations and areas for future improvement. One key challenge is the scalability of the model architecture and pretraining dataset. As the size and complexity of spatial single-cell datasets continue to grow, there is a need for more efficient and scalable training approaches, such as distributed computing and model parallelism.

Another area for future development is the incorporation of explicit spatial coordinates during pretraining. While Nicheformer currently learns spatial relationships implicitly through the co-occurrence of cells in the pretraining dataset, incorporating explicit spatial information, such as cell locations and tissue morphology, could further enhance the model’s ability to capture spatial patterns and dependencies.

Improving the interpretability of Nicheformer is also an important direction for future research. While the model has demonstrated strong performance on downstream tasks, understanding the learned representations and the factors driving its predictions remains a challenge. Developing tools and techniques for visualizing and interpreting the model’s internal representations could provide valuable insights into the biological mechanisms underlying spatial cellular variation.

Need for Standardized Benchmarks

As the field of foundation models for spatial single-cell biology continues to evolve, there is a growing need for standardized benchmarks to evaluate and compare the performance of different models. Currently, the lack of well-established benchmarks makes it difficult to assess the relative strengths and weaknesses of different approaches and to track progress over time.

Developing a comprehensive suite of benchmark tasks and datasets that cover a wide range of biological systems, experimental conditions, and data modalities would enable more rigorous and systematic evaluation of foundation models like Nicheformer. These benchmarks should include both spatial prediction tasks, such as those explored in the Nicheformer paper, as well as more traditional single-cell analysis tasks, such as cell type identification and trajectory inference.

Establishing standardized benchmarks will facilitate the comparison of different models, highlight areas for improvement, and accelerate progress in the field. It will also promote reproducibility and enable the community to build upon the most promising approaches and best practices.

In conclusion, Nicheformer represents an exciting advance in the application of foundation models to spatial single-cell biology, but there is still much work to be done. By addressing the limitations and challenges outlined above, and by establishing standardized benchmarks for evaluation and comparison, we can unlock the full potential of foundation models for understanding the complex spatial organization of tissues and advancing biological discovery.

This post was written with the help of Claude 3 Opus.

Leave a comment